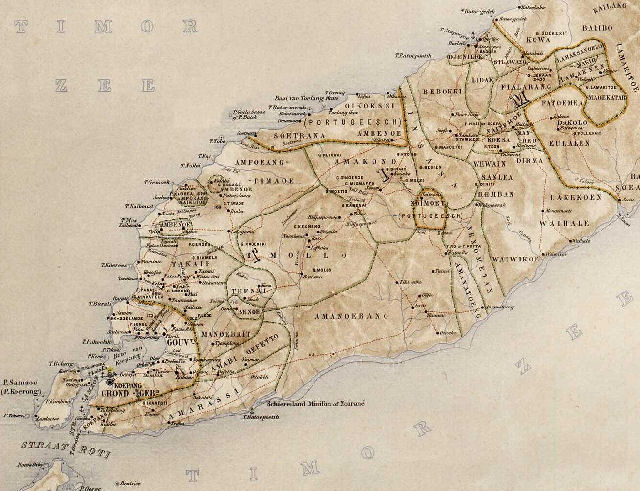

Timor Barat, land of the Atoni - and some othersWe have already remarked upon Timor's ethnic diversity in the article on the island as a whole. This diversity is most extreme in East Timor, but West Timor also has many ethno-linguistic groups. The dominant groups, in order of importance, are the Dawan speaking Atoni, divided into seven main dialect groups, and the Tetum or Tetun speaking Belu, an ethnic group that immigrated into Timor from areas near the Malacca Straits in the 14th C., and crosses over into central East Timor. Less important language groups are the Helong, remnants of a group thought to predate the Atoni, many now living on the small island of Semau; the Papuan-related Bunak; and the Rotinese and Savunese who were imported by the Dutch colonial regime to run the colony, and who, on account of their education and generations of experience in administration still form a population segment with an importance far out of proportion to their limited numbers. Bahasa Indonesia is widely spoken, especially by the young, but is not yet universally understood, many elderly people especially have only their own local dialect, and perhaps that of their neighbours. Some 90% of the West Timorese are Christian, mostly Protestant, but under the veneer of Christianity many maintain animist beliefs and practices. Each clan is associated with one or more plant or animal totems that figure in its myths of origin, which are taboo for them to cut, kill, leave alone eat, and are often used as an emblematic motif in its textiles. Many still make and wear ikat, not just for ceremonial occasions, but in many regions also for daily attire.

Ikat weaver in West-Timor. Photographer unknown, early 20th C., Tropenmuseum of the Royal Tropical Institute (KIT), Creative Commons Licence. When we visited Timor in the early 1980s, while attempts were made by development agencies to 'industrialize' ikat (meaning mechanisation and rationalization, i.e. abandonment of symbolic content and other links with tradition), most weaving was still practiced under the same primitive circumstances, and with the same adherence to tradition. The lives of the majority of the West Timorese are still hardly touched by modernity. Health services, education, public transport, and communication infrastructure, where on offer, are very poor. Most of the islanders practice low-yield ladang (slash and burn) agriculture, producing corn, cassava, sweet potatoes and some rice, which at best allows them to subsist, because geography and climate collude to make agriculture hard and unrewarding. To enrich their menu buffalo, cattle, pigs and chickens are reared as the local circumstances allow. As most everywhere in Nusa Tenggara lontar palm also plays an important nutritional role, and betel nut is grown because of its importance in ritual - which outsiders might deride as a centuries old justification for maintaining addiction. Timor Barat is a rugged, mountainous country, with the mountains getting higher

The dry season, also called the 'hungry season', leaves the islanders with little to do but repairing their houses, attempt some trading, and share their yarns as they wait for better days. When the 'better days' come, in the form of often torrential rainfall, flash floods, landslides, and swept away bridges are common. Still this is a period of new hope, as the fields can be planted and soon turn green. The end of the rainy season is harvest time, and time for celebration. Recent advances in water management, mainly focused on the construction of small dams, help conserve some of the abundant rainfall of the wet season and improves farmers' incomes. The northern coastal zone, reminiscent of Australia, is largely dry and barren, and beyond improvement by water management; part of the mountainous interior is thickly wooded; some of the humid southern parts are quite lush, the coastal basins of the Belu quite fertile. Prior to European intrusion,Timor was organized into numerous tiny kingdoms, each comprising some five to thirty villages, i.e. 500 to 10.000 people. The Dutch changed the power structure dramatically by appointing rajahs, who had complete power over large tracts of land, and could lord it over many formerly independent kings, but were themselves subordinate to the colonial governor. All of these kingdoms had their own traditional ikat patterns, by which the wearers could distinguish themselves. Most West-Timorese ikat textiles, including those for ceremonial use, take the form of clothing: tubular sarongs for the women, and oblong wraps for the men. Today many West-Timorese men still wear traditional ikat cloths, some daily, others just on festive occasions, and though the rigid adat rules prescribing what motifs may be woven by whom are not adhered to as strictly in the past, on the whole the Timorese have stuck to their regional patterns. Ikat textiles of Western TimorWest Timor is somewhat underrepresented in the collection. When we first started collecting, the market, especially the Balinese market, was flooded with man's wraps of type 2 (see below), many of them indifferently made, and rather gaudy looking due to their flanking panels done with chemical dyes. This had the effect of turning our eyes towards other regions. It was only in more recent years that we discovered the wealth of motives and refinement that West Timor has to offer. We aim to address the deficit in the coming years - not an easy task as superior pieces now are hard to find. Man's wraps - six regional typesThe wraps for men, called selimut in Bahasa, locally go by a range of different names such as beti naik, mau naik and tais mane. Most West-Timorese ikat is made on very narrow looms, rarely exceeding 75 cm in width, and sometimes as narrow as 30 cm, so that a fair sized selimut requires two or three panels stitched along the selvages.Atoni selimut usually consist of three panels, with a central panel that contrasts in technique, colour, or both with the side panels, which tend to be red or consist of a number of narrow stripes of different colours that when seen from some distance come across as red. Those from Amanuban and neighbouring areas have ikated centre fields, those from the northern and western Atoni regions have white centre fields. Tetum selimut generally consist of two panels, though the design may mimic a three panel format, probably as three is considered a holy number, standing for the place of origin, and the places on either side. Yaeger and Jacobson differentiate six basic design types for West-Timorese man's wraps, and indicate the regions where they are most prominent. Where available we illustrate the types with examples from the Pusaka Collection. |

| 1. Three panels, central panel fairly narrow and white, with or without decoration in buna. The historic dress of the Atoni. Regions: Molo, Miomafo, Amfoang, Biboki, Insana, and also Ambenu - actually in East Timor, but culturally part of Atoni territory. The significance of the white centre field is the subject of speculation. One likely reason for its continued popularity is that in Atoni culture white stands for virility and other qualities associated with a warrior, whereas black (dark indigo) stands for female attributes. Example: PC 159, PC 182. |

|

|

| 2. Three panels, the central one ikated in indigo or indigo overdyed with morinda, the side panels decorated with narrow stripes usually in bright colours, predominantly red. Regions: Amanuban, Amanatun and neigbouring parts of Miomafo, Molo, Insana and Biboki. Those from Amanutan and Miomafo usually have an ikat design stripe in each side panel. Example: PC 013. |

|

|

| 3. Two panels, multiple longitudinal narrow stripes with fine motifs. Regions: Atoni areas bordering Belu: Biboki, Ambenu, Maubesi, Insana. The number of design stripes is most commonly eight, more rarely two, four or eight. Some cloths of this type have an odd number of design stripes, one of the panels being wider than the other to accommodate the additional stripe. This may be seen on older cloths from Biboki, and these days on wraps from Ambenu. Examples: PC 132, PC 095, PC 095. |

|

|

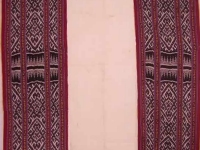

| 4. Two panels, each with a longitudinal ikated band of around 5-10 cm width in between narrow stripes. Known as Belu style. Regions: Tasifeto, Malaka, Lamakman, Biboki, and also in the East-Timorese enclave of Ambenu (as well as in much of the rest of East Timor). Examples: PC 120, PC 137. |

|

|

| 5. Two panels, both with ikat on one half, plain black or dark indigo on the other, producing a cloth with dark middle section, and visually a tripartite aspect. Regions: Insana, northern Amanutan, and some localities scattered across the Belu area. This may be an archaic type, a legacy of the Melu ethnic group which was displaced by the Tetum in the 14th C. Example: PC 081. |

|

|

| 6. Two panels, mirror images of each other, with ikat patterns over the entire surface. Regions: Not the dominant type anywhere, but found in most areas of Timor where ikat is made. Most common in Amanuban, especialy Niki-Niki and Oinlasis, where they are generally executed in indigo only and are decorated with human figures, crocodiles, scorpions or other animal motifs. Also found in the East Timorese enclave of Ambenu, and in Lamakman where motifs tend to be geometric and the background black. Example: PC 005. |

|

Tubeskirts - sarong - three basic typesWhile there are several different types of tubeskirt worn on Western Timor, only three rely on ikat as the main technique for decoration. Most are similar to the selimut from the same area. The numbers correspond with the styles of man's wraps shown above. |

|

2. Central ikat panel flanked by stripes. Usually fairly short and wide, therefore practical. Simpler ones are the same as selimut from the area, but sewn into a tube. Some, especially later examples, show ikat patterning all over, and may have only two panels. Found in same areas as selimut with central ikat panels: Biboki, Amananuban, Miomafo, Amanutan. Regions: Atoni areas bordering Belu: Biboki, Ambenu, Maubesi, Insana. | |

|

1 & 3. Sarongs with ikat stripes. Regions: Biboki, Amarasi, Ambenu, western Miamafo. These types of tubeskirts have multiple ikat design stripes of varying width, often interspersed with plain stripes. Those from Amarasi resemble the selimut from the area without the white central area. Their lay-out sometimes shows a similarity to sarongs from Savu or Flores. | |

|

4. Belu style sarongs. These commonly comprise two or four panels, with a striped centre, flanked by an iketed band and plain colour borders. In Insana the design is invariably tripartite, whatever the actual number of panels. Regions: Belu, Biboki, Insana, northern Amanutan. Long (well over 2 meters) and narrow four panel sarongs are made for ceremonial use and as bridewealth. Example: PC 133. |

Great wealth of motifs

The figurative motifs of the West Timorese weavers cover the entire range of the natural world: human figures, plants, and animals, all with totemic significance. The most common and important of these are crocodiles, representations of Uis Neno, the animist supreme being. Also frequently depicted are lizards, frogs, chickens, particularly the cherished fighting roosters, jungle fowl and other birds. As the Atoni are highland people with little interest in the sea, aquatic animals other than crocodiles (in Indonesia usually salt water crocodiles) are rarely woven into their cloths. |